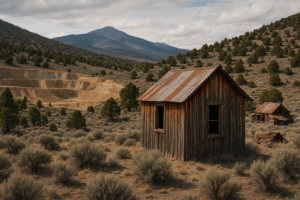

The wind across eastern Nevada carries whispers — not of traffic or casinos, but of pickaxes, wagon wheels, and voices from a century ago. Hidden among White Pine County’s high-desert mountains are the ghost towns that once defined the Silver State’s boom-and-bust rhythm. If you’ve ever felt drawn to places where history still breathes through broken windows and weather-worn signs, these towns tell that story in rust and dust.

According to TripAdvisor: “Small but rich with mining artifacts and local stories—worth a stop before your ghost-town loop.”

Explore White Pine Public Museum on Google Maps

Travelers driving U.S. Highway 50 — the Loneliest Road in America — often pass through Ely or Eureka without realizing how many vanished communities lie just beyond the sagebrush horizon. Each is a snapshot of ambition, hardship, and fleeting fortune. Today, exploring the White Pine County ghost towns means uncovering layers of Nevada’s mining heritage while standing in landscapes that remain almost unchanged since the 1870s. Round out your trip with heritage railways, classic hotels, and small-town events from Historic & Cultural Experiences in Nevada. Follow the cowboy connection on Cowboy Heritage Trails. Plan your driving loop using historic drives between Reno and Las Vegas. Expand to neighboring states with scenic USA road trips for every season.

The Birth of Boomtowns

Silver Dreams and Mountain Fortunes

The discovery of silver near Treasure Hill in 1868 sparked one of Nevada’s most dramatic rushes. Prospectors poured into the region, pitching tents that soon turned into saloons, hotels, and newspaper offices. Within a year, the town of Hamilton rose from wilderness to a city of more than ten thousand residents.

Stagecoaches thundered along rutted roads, ore wagons creaked toward smelters, and miners worked by candlelight inside narrow tunnels cut through icy rock. Fortune favored few, but hope held everyone. The area’s remoteness didn’t matter — ambition was the only currency stronger than silver.

When fire swept through Hamilton in 1873, many rebuilt, but the second blaze in 1885 finished what greed and exhaustion had begun. Families moved on, buildings fell silent, and snow reclaimed the streets. What remains today are stone foundations, fragments of brick chimneys, and a sense that time never truly left.

Hamilton and Treasure Hill: Echoes of a Silver Empire

Exploring Hamilton’s Ruins

Reaching Hamilton requires patience and a sturdy vehicle. A dirt road climbs through the White Pine Range, winding past juniper and piñon before opening into a plateau of scattered ruins. The air is thin, the silence deep. As you walk through what was once the business district, you’ll spot the faint outlines of storefronts, a crumbling jail, and the remains of the courthouse that burned twice.

Visitors often describe the site as hauntingly peaceful. From the ridge above town, the panorama stretches for miles — the Ruby Mountains shimmering to the north, Great Basin National Park’s peaks to the east. It’s easy to imagine the sound of hammers and laughter drifting across the valley.

Bring water, good shoes, and respect; Hamilton sits at nearly 8 000 feet, and weather changes fast. Yet even in summer, the breeze feels cool — as if drawn straight from the tunnels below Treasure Hill.

The Treasure Hill Bonanza

A short drive above Hamilton leads to the legendary Treasure Hill mines. At their peak, they produced millions in silver within months. Miners tunneled deep into the mountain, building entire underground neighborhoods lit by lanterns. In winter, snow cut off supply lines, forcing residents to rely on ingenuity and grit.

Today, rusted headframes and collapsed adits mark the slopes. The Bureau of Land Management allows responsible exploration, though most shafts are sealed for safety. Still, you can walk among the ore dumps and imagine the feverish nights when men swore they could hear silver veins singing beneath their feet.

Eberhardt and Treasure City: Forgotten Sister Settlements

When Hamilton thrived, Eberhardt and Treasure City rose nearby, forming a triad of prosperity. Eberhardt was known for its quartz mills; Treasure City, perched high on the mountain, boasted lavish hotels and a theater.

Within a few years, both towns faced the inevitable — ore depletion and the lure of new strikes elsewhere. By 1874, the population plummeted, leaving only wind to wander the streets.

Hikers can still trace wagon paths linking the sites. Stone walls mark old property lines, and broken bottles gleam in the sun like relics of vanished celebrations. The sense of isolation is profound; standing amid the ruins, you realize how thin the line was between wealth and wilderness.

Travel Tips for Modern Explorers

Getting There

From Ely, head west on U.S. Highway 50 for 10 miles, then turn onto NV-882 (signed Hamilton Road). The route is gravel for most of its 30-mile climb. Four-wheel drive isn’t essential in dry weather but recommended after rain or snow.

Always check conditions with the Ely Ranger District before you go. Cell service fades quickly, and temperatures can drop 30 degrees between town and the mountain top.

What to Bring

Plenty of water and snacks — there are no services at any site.

A printed map or GPS download (signal is unreliable).

Camera and flashlight for exploring safe structures.

Layered clothing: mountain weather shifts fast.

Respect posted signs; many areas fall under private mining claims or protected heritage zones. Leave artifacts where you find them — photographs preserve the story better than souvenirs.

Safety and Stewardship

Ghost-town tourism thrives on curiosity, but safety comes first. Avoid entering tunnels or buildings with unstable roofs. Rattlesnakes, loose timbers, and hidden shafts are common hazards.

Local historians in Ely encourage visitors to document, not disturb. Share your photos with the White Pine County Museum — they often use traveler images for restoration reference. Every respectful visitor helps keep Nevada’s history visible for future generations.

Cherry Creek – The Town That Refused to Disappear

Gold in the Hills

North of Ely lies one of Nevada’s most enduring ghost towns — Cherry Creek. Founded in 1872 after rich gold discoveries, it quickly grew into a thriving settlement of saloons, boardinghouses, and hopes as bright as the ore pulled from its mountains. For a short while, Cherry Creek rivaled Hamilton in excitement.

Miners tunneled deep into the Cherry Creek Range, building wooden headframes that still cling to the slopes today. Unlike other boomtowns that flared and vanished, Cherry Creek endured multiple revivals. Each time the price of gold rose, prospectors returned, raising tents where wooden hotels once stood.

A Blend of Ghost and Living Town

What makes Cherry Creek special is its ability to hover between past and present. A few families still live among the ruins, maintaining small ranches and cabins. You can wander through collapsed barns, step into the old post office, and see a faint echo of Main Street where wagon ruts remain carved in the dirt.

Locals tell stories of a schoolteacher who refused to leave after the last class in 1912, teaching any child who wandered in for decades. They also speak of the Cherry Creek Cemetery, its iron gates creaking in the wind, where headstones bear both pioneer names and modern flowers left by descendants.

Travel Notes

From Ely, follow US 93 north for 55 miles, then turn west onto the signed dirt road to Cherry Creek. The track is rough but passable in good weather. Bring food, water, and fuel; there are no services. Mornings are quiet except for ravens calling over the ridges, and sunsets paint the hills in bands of crimson and violet.

Osceola – A Gold Rush Among the Junipers

The Longest Life of Any White Pine Camp

Farther south lies Osceola, a town that lived longer than most because its ore veins ran stubbornly deep. Discovered in 1872, Osceola once boasted a mile-long Main Street lined with hotels, a newspaper, a school, and more than two thousand people. Unlike Hamilton’s silver, Osceola’s gold kept miners digging for nearly sixty years.

The most impressive sight today is the old dredge pit, evidence of Nevada’s first hydraulic mining operation. Water was piped from the mountains to blast away entire hillsides, exposing gold-bearing gravel. The system worked until drought and falling prices ended production around 1910.

Life at the Edge of the Desert

Standing in Osceola, you understand the resilience required to live here. The settlement sits at the base of the Snake Range, facing the wide desert basin. Winters bite hard, summers bake, yet wildflowers still find cracks between the stones. A few wooden cabins survive, some with walls patched by tin and newspaper.

When the wind rushes through the junipers, it carries the scent of sage and history. Travelers often describe Osceola as less eerie than peaceful — a place where the ghosts seem content to rest.

How to Reach Osceola

Take US 6 west from Ely for 17 miles, then turn south on Osceola Road. The route is unpaved but graded; a high-clearance vehicle is recommended. The entire round trip can be done in half a day, though most visitors linger to photograph the ruined stamp mill and the view of Great Basin National Park in the distance.

Ely – The Living Heart of White Pine County

From Mining Hub to Historic Haven

Every ghost town needs a living neighbor, and Ely fills that role with pride. Founded as a stage stop in the 1870s, Ely later became the county seat and remains the gateway to Nevada’s eastern high country. The copper boom of the early 1900s brought railroads, schools, and grand brick buildings that still anchor the downtown district.

Today, Ely serves as both supply base and storyteller for White Pine County’s forgotten towns. The Nevada Northern Railway Museum preserves steam locomotives that once hauled ore from these mountains. Visitors can ride restored trains through the desert — a living history experience that links the modern traveler to miners of a century ago.

Visitors on TripAdvisor describe it as “an unexpectedly immersive ride through rails, mining and history—make time for the steam-train trip.”

Explore Nevada Northern Railway Museum on Google Maps

White Pine County Museum and Historical Society

To truly appreciate the region’s ghost towns, spend time at the White Pine County Museum in Ely. Its exhibits include mining equipment, photographs, and journals from Hamilton, Osceola, and Cherry Creek. Volunteers—many descendants of early settlers—share stories that bring the artifacts to life. A recreated blacksmith shop and pioneer cabin give context to the ruins scattered across the hills.

The museum also coordinates heritage driving tours. Maps trace routes linking major ghost towns, highlighting safe access points and scenic lookouts. Pick one up before setting out; it transforms wandering into understanding.

The Culture of Preservation and Storytelling

Guardians of the Past

White Pine County’s residents have a deep respect for their ghost towns. Rather than fencing them off, they maintain a quiet guardianship. Volunteers repair signage, clear debris, and install interpretive panels describing who lived where and why they left.

Each summer, the Ely Renaissance Society hosts a weekend called Ghost Days. Locals dress as pioneers and miners, guiding visitors through exhibits, plays, and storytelling sessions. Children learn to pan for gold while elders recount family legends of wagon journeys and mining strikes.

Explore Ely Renaissance Village on Google maps

On TripAdvisor guests comment: “A cozy heritage hub with murals, stories and ghost‐town maps—perfect orientation for the region.”

Education and Community Pride

Schools incorporate local history into lessons, taking students on field trips to Hamilton’s courthouse ruins or Cherry Creek’s cemetery. For many families, these aren’t just field trips—they’re pilgrimages to the places their ancestors helped build. History here isn’t confined to textbooks; it’s visible on every ridge.

Responsible Exploration

With renewed interest in rural tourism, White Pine County emphasizes Leave No Trace ethics. Visitors are encouraged to photograph, not collect; to walk carefully; and to support Ely’s small businesses in return for their stewardship of the past.

Coffee shops display local photographers’ prints of ghost towns in winter snow. Craft stores sell handmade jewelry inspired by old mine timbers. Every purchase helps sustain preservation work across the region.

A Road Trip Through Time

The Ghost-Town Loop

Exploring White Pine County’s ghost towns is best done as a road trip. The routes are quiet, the landscapes vast, and the sense of discovery unmatched. Most travelers begin in Ely, the county’s only sizable town, where supplies, lodging, and local knowledge are easy to find.

From Ely, you can trace a loop of roughly 150 miles that connects Hamilton, Treasure Hill, Cherry Creek, and Osceola. Plan for a full day if you want to see them all, or two days if you prefer time to linger. The roads are mostly gravel but well-graded; even a modest SUV can manage them in good weather.

Start early, when the mountains blush pink at sunrise and the temperature still holds the night’s cool breath. The first stop is Hamilton, high in the White Pine Range, then continue to Treasure Hill, Eberhardt, and Treasure City before looping north toward Cherry Creek. Finish with Osceola before returning to Ely for the night.

Suggested Two-Day Itinerary

Day One – Silver Dreams

Morning: Depart Ely for Hamilton (approx. 35 miles). Walk through the courthouse ruins and photograph the stone walls against the sky.

Midday: Picnic among the sagebrush on Treasure Hill; the view stretches forever.

Afternoon: Continue toward Eberhardt and Treasure City; both are accessible by connecting trails. The road is rough but rewarding.

Evening: Return to Ely for dinner at Cellblock Steakhouse, located inside a historic jail building — a playful nod to Nevada’s frontier days.

Day Two – Gold and Quiet

Morning: Drive north to Cherry Creek. Stroll through the post office ruins and cemetery.

Midday: Head back south on US 93 to the Osceola turnoff. Spend the afternoon walking around the dredge pit and cabins.

Evening: Return to Ely. End the trip with a ride on the Nevada Northern Railway if schedules allow — a perfect finale to a journey through time.

The Overlook at Hamilton Ridge

From a switchback just before Hamilton, there’s an unmarked pullout where you can see the entire valley spread below. The view at sunset is unforgettable — sunlight turning sage into silver and the mountains into shadowed walls.

Cherry Creek Cemetery

While visiting graves requires sensitivity, photographers appreciate the way the wrought-iron fences cast lace-like shadows at dawn. Always be respectful and leave everything undisturbed.

Osceola’s Dredge Basin

From a small hill above the pit, the contrast between yellow grass, rusted machinery, and the blue sky creates perfect compositions. In spring, wild irises bloom among the tailings, adding unexpected color.

Ely’s Murals

Don’t miss the downtown murals created by the Ely Renaissance Society. Each one depicts a moment from county history — miners, trains, and Basque dancers — turning city walls into open-air museums. They make wonderful backdrops for travel photography that connects the ghost towns to modern life.

Where to Stay and Eat

Lodging in Ely

Hotel Nevada & Gambling Hall: Built in 1929, this historic hotel offers themed rooms and old-West charm. Even if you don’t stay overnight, step inside to see vintage photos and memorabilia.

La Quinta by Wyndham Ely: Modern comfort with easy access to Highway 50 and local restaurants.

KOA Ely Campground: A clean, friendly base for road trippers and RV travelers.

Local Dining

Cellblock Steakhouse: Excellent steaks served in a playful jail-themed setting.

Economy Drug & Soda Fountain: A nostalgic lunch stop for burgers and milkshakes.

Racks Bar and Grill: Friendly pub fare, ideal for travelers returning from the trails.

Cupit’s Coffee House: Locally roasted blends and pastries perfect for early departures.

Eating locally helps sustain Ely’s small businesses, which in turn fund historical preservation and ghost-town signage throughout the county.

Tips for Responsible Exploration

Preserve What You Photograph

Never remove artifacts, no matter how small. Even a single bottle or rusted nail contributes to the story archaeologists and historians continue to study. Photograph instead; every image keeps the landscape intact.

Travel Prepared

Fuel up before leaving Ely — gas stations vanish beyond town limits. Carry extra water, snacks, and a spare tire. Weather shifts fast; even light rain can turn desert clay into impassable mud.

Learn Before You Go

Stop by the White Pine County Museum or visitor center for current road updates and heritage maps. Staff members love to share lesser-known directions, including routes to smaller ghost camps like Ward or Taylor, both hidden near the mountains.

Reflections: The Spirit That Stays Behind

Standing amid the ruins of Hamilton or Cherry Creek, you sense that history here isn’t gone — it’s resting. Every shattered window frame, every toppled chimney holds a trace of human ambition and endurance. The wind that sweeps through these canyons feels ancient yet alive, carrying whispers of pickaxes, laughter, and loss.

White Pine County’s ghost towns remind travelers that progress doesn’t always mean forgetting. Sometimes, it means learning to listen. The miners may be gone, but their legacy still echoes in the mountains, the museums, and the stories told by those who remain.

In an age obsessed with speed, these empty streets offer something rare — silence that speaks. It’s the silence of memory, of endurance, and of the desert itself. If you leave with dusty boots and quiet awe, you’ve heard exactly what these ghost towns have to say.

Frequently Asked questions About Visiting White Pine County Ghost Towns

Hamilton, Cherry Creek, and Osceola are the most accessible and historically rich. Smaller sites like Eberhardt and Treasure City offer deeper exploration for adventurous travelers.

Most mine shafts are sealed for safety, and entering abandoned structures is discouraged. Enjoy the views from outside and stay on marked paths.

Late spring and early fall provide mild weather and clear roads. Summer can be hot at lower elevations, while winter brings snow to higher passes like Hamilton.

Yes. The White Pine County Museum and the Ely Visitor Center offer free driving-tour maps linking all major sites.

Some local historians offer seasonal tours during Ghost Days or by arrangement through the museum. Contact ahead for schedules.

Locals share stories of lantern lights seen at night near Hamilton and faint music in Cherry Creek, but most visitors experience peace rather than fear. The history itself provides the mystery.

Water, food, sun protection, sturdy shoes, a camera, and a printed map. Cell coverage is limited in most areas.

Yes, dispersed camping is permitted on Bureau of Land Management land near most sites. Practice Leave No Trace principles and pack out all trash.

Donate to the White Pine County Museum or the Ely Renaissance Society. Buying local art or souvenirs in Ely also helps fund ongoing restoration.

They preserve the story of Nevada’s early settlers — people who chased silver and gold, built communities from nothing, and left behind lessons about resilience and change.